Last year I lied my way into a psych ward. I lied during the intake evaluation, then I lied to the nurses. I stopped lying when they led me into the break room, where everyone was watching replays of Trump's attempted assassination.

All eyes were glued to the TV, it was a shocking moment, a violent spectacle, with blood and fear and a gunman who was shot dead by other men with guns. In this room, whoever held the remote held the power, and the power was with Bob. Bob was an old skinny white man who, as I came to find, would always wear the same oversized t-shirt with stains and grey sweats. He often would turn the volume up so loud that it became untenable for the older women who would leave, shuffling in their socks, heads nodding side to side, as though Bob were committing a real felony. In my opinion his only offense was muttering that the gunman should have killed Trump. A boy named Benny with wide eyes sat next to him, egging him on, stating that the whole thing was staged, that Trump should have been blasted. I remember looking around at the rest of the room still watching (too many) replays of the bullet grazing Trump's ear, before standing up myself and saying, "He looks badass," and walking away to catch up with the ladies. Not yet out of earshot someone added, "He does look like a hero," as Benny finally shut up.

There were always a couple hours in the afternoon to do nothing. Free time, they called it. Thirty minutes allotted for phone use, which everyone looked forward to. I could tell because I never saw them move as quickly as when the clock struck the hour. All at once, they'd seek out the attendant whose job it was to hand out phones, after getting signatures and dating a piece of paper to acknowledge the use of their own devices.

Some patients ran.

Wearing long blue hospital gowns and sticky socks that occasionally stuck on the carpet. They moved like children chasing ice cream. They were addicts. Here because of a different illness but the dopamine reigned supreme.

Even the boy with jizz stains and drool in his beard got up from the single computer to spend time on his phone. If you checked out a phone, you had to use it in the cafeteria. It was a sterile room kept cold for no reason besides poor HVAC zoning controls, the nurses said. It had vinyl tile flooring, white plastic chairs and fake wooden tables. The books kept there were sticky and each puzzle had missing pieces. I stayed in the TV room, which was small, with chairs pushed against the walls. It opened to a middle artery that housed the nurse station and entryways into two separate halls where we slept. Men and women in separate rooms, though the rooms were next to each other. You could hear sounds easily at night. The insulation was inadequate and did not stop screams or crying or other masturbation sounds. In the TV room the chairs were somewhat comfortable, having been sat on many times, they usually made a sound. Not real leather, but the frames were wood.

It could have been worse.

Being a madwoman in the olden days meant you might be shackled to a wall or left in a decrepit cell to rot alongside ten other tightly packed madwomen. Hospitals for the insane were not places of healing, but rather confinement. At the notorious insane asylum Bethlem Hospital, torture existed as a form of medicine. Patients were routinely kept in chains, beaten, whipped, and laughed at by the public who could enter with a penny or two to scoff at the entertainment. Next to that, today's hospitals are infinitely better. Medicine always improves, at least in its trajectory. Surely modern-day psych wards are superior to old ones from centuries ago.

After reading Carla Yanni's "The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States," I'm beginning to wonder. Her book focuses on 18th and 19th century architecture and how it informs the function of a space and treatment within. My goal in this essay is to discuss historical ideas and propose new ones. I will ultimately describe a vision of psychiatric care that is better and possible.

Philosophy of Design

Traditional design tells us that how a space comes together matters on a sensory level. It's indisputable that spending time in beautiful places affects the body in a positive way, just as perceiving certain things can invoke repulsion. If you are not a fan of bright lights, or the starkness of white walls, you are not alone. Visiting La Sagrada is a spiritual experience. I do not need to go into the details. Good design is a feeling. A mood can spring from a glance at an object. Even a stain on a wall.

When designing mental hospitals, attention to the sensory experience is crucial. Awareness of what is around us gives greater awareness of ourselves, because we understand our place in it. Inpatient care is defined by limitation, and patients feel less free—because they are.

Modern day architects who specialize in healthcare often say their focus is to optimize a calm environment, with natural light, nature, privacy, safety, inclusive spaces, and opportunities for social interaction.

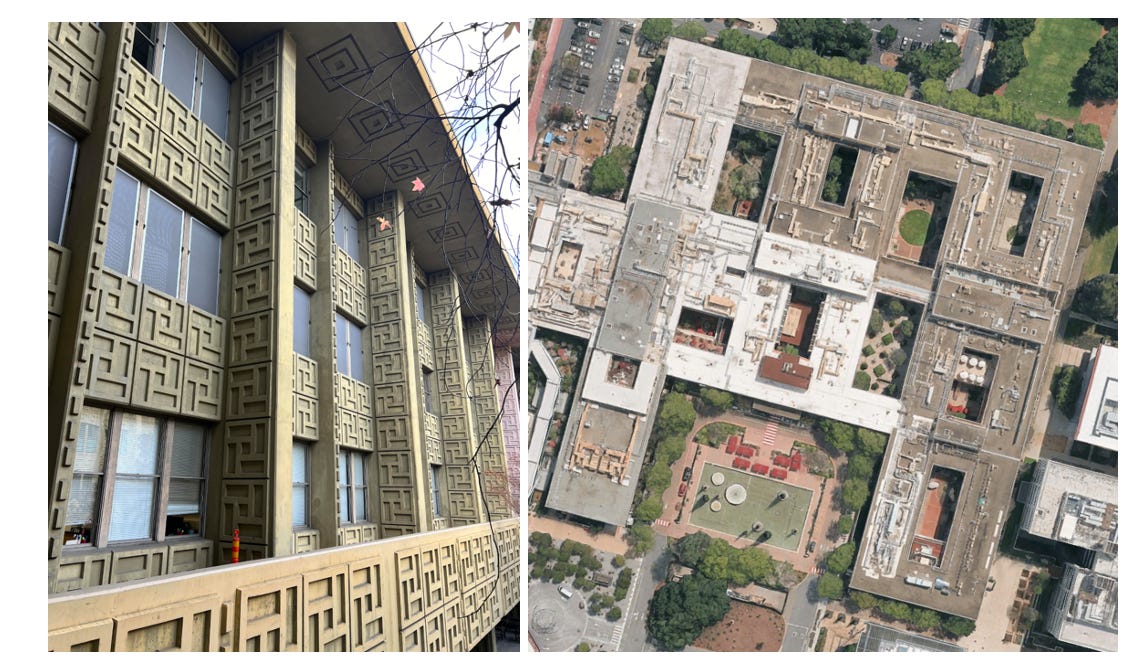

While the architect Kaplan Mclaughlin Diaz (KMD) has a website with impressive mockups, the results are less appealing. The Psychiatric Health Facility at Kaiser Hospital in Santa Clara was completed in 2015 but looks like it's stuck in the 90's. Carpeted throughout, with sterile LED lights, the space includes a cafeteria, offices, classrooms, and a small outdoor area. Patient rooms have windows that allow natural light however privacy film is applied which obstructs visibility outward. When I stayed there only the top portion of the windows were without film. I could look out at the branch ends of nearby trees. The bathroom door had a picture of the Dolomites. My experience of nature was suboptimal, to say the least.

One of our nation's leading hospitals, Stanford Hospital, also tried to incorporate nature. In 1959 Edward Durell Stone was hired to create a hospital with open spaces and natural light. He approached the incorporation by using stonework and inner courtyards to maximize views and light. Patients at the Inpatient Psychiatry Service (H2) are privy to views of concrete facades and the Bing Garden. The interior includes rooms shared by patients of the same sex, connected to a main hallway. Window film is applied for privacy, diminishing outward visibility. Men and women can mingle in a break room which has a TV and tables for eating. Lighting is LED, flooring is vinyl, and walls are white. Access to the garden is only for certain patients at certain times.

There are places that do not have gardens. The Idaho Maximum Security Institution in Boise is one of them. It is managed by the Department of Corrections, though nurses and doctors work there. This care setting is for (non-criminal) patients with a serious mental illness, like OCD, BPD, PTSD, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. It is a maximum-security prison cell, originally built for the purpose of confining violent offenders.

Seeing this space, knowing that a patient is living there today, should remind you that psychiatric facilities are places of great suffering. With an average stay of three to five months, I do not need to waste time presenting facts about the impact of conditions like the above on a well-functioning brain, no less one already in spiral. I will take two more sentences to condemn this place, though. Boise is ingraining negative behavioral tendencies that disrupt a person's ability to rejoin society. Intents be damned, this is not healthcare, this is torturous. After a news article exposed these conditions in 2023, state legislators speedily approved $25 million for a new facility with 26 beds. Though two years later, a construction timeline remains unknown.

Speaking of torture, the oldest psych ward—Bethlem—was founded outside London in the 1200's as a religious institution that raised funds for crusaders who fought in the Holy Lands. Over time it became a hospital for the insane. In 1674, Robert Hooke designed a new building which notably had spaces for the breeze to enter, and airing courts (outdoor areas). Men and women were kept separate and food shortages and restraints like leg locks and handcuffs were common. Bethlem allowed the public to enter and taunt inmates in exchange for a small fee. Treatment included rotation therapy (being spun in circles to induce vomiting), starvation, beatings, confinement, ice baths and bloodletting.

Before Bethlem the insane roamed free until rounded up and thrown in prison along with the poor and other unruly or naked characters. They were also put on boats which floated from harbor to harbor, known as ships of fools. These ships were somewhat novel, as they allowed for both confinement and mobility. A moving container amid a backdrop of fresh air and endless blue water gazing. We can almost call it a therapeutic model.

There was an important event in the 18th century which had a significant effect on the philosophy of caring and designing for mental health—The French Revolution. Ideas swirled around liberty, equality and fraternity, which eventually made their way into the minds of those in charge of building hospitals. Conditions at Bethlem had such negative lore they also spurred a reaction. News traveled from Europe to America that physicians were removing shackles on mental patients. Philip Pinel famously promoted moral treatment at Bicêtre Hospital, where he started a program that included better food quality, new beds, and an exercise routine.

America got inspired.

Though they were not the only ones. Following the Scottish Enlightenment (1740-1790), the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh spent considerable resources competing against each other to create the best asylum. London's St. Luke hospital was also conceived following a design competition (1777). In America, thinkers philosophized about medicine and the belief that an asylum itself could be therapeutic. Modern city life was thought to be inherently stressful and damaging to the psyche, with nature looked at as a literal cure. Behavior was thought to be explainable by studying the surrounding environment. There was suddenly new effort to undo evil approaches of the past. Caring for the sick became recognized as a civic duty and religious institutions and groups carried the banner with pride.

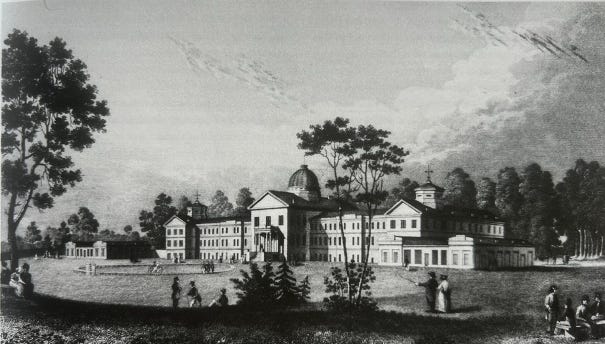

One of the earliest examples of new thinking was Pennsylvania Hospital, built in 1770.

Situated in Pennsylvania, it was founded by Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush to accommodate both medical and mental cases, believed to be separate at the time. It included an intricate foyer, grand staircases, a library, a steward office, an apothecary (pharmacy) shop, a parlor and resident areas for staff. On the third floor was a theatre with capacity for 300 seats. Patients deemed insane were housed separately and took their meals in the basement. Men and women comingled in common areas though had separate day rooms. While psychiatric patients were not treated equally compared to medical patients, this hospital provided a respectable setting.

Nearly 100 years later, America tried a more radical model.

A coffee merchant named William Tuke founded The York Retreat in 1796. He was inspired to build after the death of a fellow Quaker, Hannah Mills, who died mysteriously in York Lunatic Asylum after entering due to depression following her husband's death. Tuke believed an open environment and humane conditions could help cure patients. The word 'retreat' was intentionally used to invoke the idea of a refuge away from the ills of society. Care included maintaining bodily hygiene, familiar meals, entertainment, encouraging sleep and requiring a daily regimen. Its location sat atop a hill with views of woods, meadows and streams. Trimmed hedges served as fencing and cows often grazed nearby.

Tuke's grandson, Samuel, followed in his footsteps and founded The Friends Asylum in 1817. It was private for Quakers, outside Philadelphia. Built with a promise of bringing "internalized self-respect and limited use of harsh bodily treatments," the house included gender-divided parlors, a reception and office. Spaces were light and airy with ventilation. Entertainment was considered part of care, the retreat had billiard tables, a garden, croquet courts and a nine-hole golf course. Airing courts on either side held animals like rabbits, seagulls and chickens as they believed "interacting with these creatures awakened benevolent feelings in patients."

America continued to try new things. In 1856, the state of Michigan built the Kalamazoo Farm Colony.

This experiment brought to the forefront the idea that labor is important to health. Purpose was recognized as tied to work, and ability, a domain of some control. Religious thought includes this with the origin of man taking care of the Garden of Eden. Heavy stone, Romanesque buildings, and porches were main features of cottages that became an experimental farm colony. The building's plan included wings on either side, with additional buildings added over time, including a chapel. 200-acres of adjacent farm was later purchased, and a wooden house was built for male patients. The Annual Report for 1895-96 boasted of success saying, "the patients living at this farm are of the agricultural class, are allowed the liberty of the entire premises and are healthy and apparently happy…in many cases there has been a marked improvement in mental and physical health after the transfer."

Due to a growing population and demand, America continued building asylums. As of 1875, there were 71 in 32 states.

Today we have 846 psychiatric hospitals. Since 1960, beds for inpatient care have reduced from roughly 525,000 to 60,000—a 90% decrease. Meanwhile the country's population has grown from about 152 to 342 million people.

America has lost the plot. We lost it decades ago. The Community Mental Health Act of 1963 led to the deinstitutionalization of psychiatric facilities. It was a marvelous idea, to drive patients out of state-run institutions and into ones in their local communities. However, centers were not prepared, half not even built, and patients became unhoused or improperly cared for.

Why Build in Nature

Architects stress the importance of biophilia in designs because it caters to the unconscious connection and feeling of comfort and desire to be in a space. Nature and the outdoors provide a sense of intrinsic freedom. Sightlines offer visuals of hope and a sense of possibility that harkens back to a universal spirit of wonder, an embedded awe of something. Big, beautiful things create humility, and problems are lost in the context of a picturesque scene. Architecturally speaking, ground-up development allows for pliable footprints and, importantly, an open layout to approach space planning with creativity for outdoor therapies—which America needs more of.

Though cities are dense and support larger populations, the availability of land is scarce. Not only is land more available outside city limits, it's cheaper. It is a sad fact that 19th century builders created open-air courts much larger than ours today, where their sizes measured ~1,000 square yards, or one sixth the size of a football field, our standard design recommendations are for ~340 square yards.

Amid the challenges, modern hospitals do try to recreate the outdoors. In Mountain View, El Camino Hospital – Scrivner Center for Mental Health & Addition Services recently underwent a repositioning of upgrades totaling $98M. Before, the building boasted a large area with natural grass, a pebbled walkway, and multiple basketball courts. Adult trees provided shade, and a green wall grew over the perimeter fencing. Post completion aerial views reveal the removal of grass and athletic courts.

While the design added eleven beds to the existing twenty-five, it removed any sense of freedom achieved from walking on the pebbled path, or sitting under a tree in the shade, or playing basketball. The architect, KMD, says they solved the need for outdoor space by creating an inner courtyard for, "patients and visitors to relax and recuperate in safe, serene, and contemplative spaces. Water features and art installations further complement the calming garden atmosphere."

Besides the rigid lines, cold concrete and fishbowl glass, my favorite detail is the tiny casket water feature. It is so dark and hard! Whoever favored that as the object to be stared at for tranquility is truly mad. Ti-Fu Tuan once wrote, "sculptures have the power to create a sense of place by their own physical presence…" What does this square embody—the inner world of depression? Does it even make a sound? Where are the soft curves of stone? My nail salon has a more soothing water fountain. And then there are the drought tolerant plantings. Heaven forbid a splash of color from perennials, or a blooming flower. If taking away real grass in favor of synthetics is the leading effort of a world-renowned architect, we are in trouble.

When the other patients ran to their phones during break, I would sit by the window and watch the birds. Outside there were many trees. One in particular held a bird feeder, and a blessed somebody would fill it periodically. With the TV muted, I could sit backwards on the chair and stare at the leaves rustling under tiny feet. There were a handful of different species, some more aggressive than others, pushing the seeds across the feeder walls, down to the ground, where the pigeons mostly pecked, looking rather dumb, next to the nimble sparrows.

Bird watching was never a thing I thought I would like. But every day it became the thing I most looked forward to. The birds were funny, the way they moved, some certainly had personalities. Knowing their prehistoric roots and watching their beaks and claws work the dirt for hidden grain was better than any TV show. It is too bad the Scrivner upgrade did not incorporate plants and flowers to invite animals, even insects, like butterflies and bees, to engage in the same space as recovering patients.

What Patients Need

An advocate for asylum reform in the 19th century named Dorothy Dix once appealed to the Massachusetts government by saying, "in many instances patients received into an asylum are taken from close confinements at home, or from dark disagreeable rooms in a jail. Being admitted from such situations, if the asylum is comfortable and pleasant, the mere change itself is soothing and restorative."

While that may describe a portion of America's population today, the greater majority of patients entering a hospital do not come from dark disagreeable rooms. They come from having freedom and agency. This is an inherent crux of care: enabling self-empowerment and realization while limiting a person's control over their own space.

Hospitals are good because they provide a secure, central location where drugs are administered by trained staff. Drugs save lives. They are vital in certain stages of care because they make immediate changes to brain chemistry. However, hospitals are also bad. They encourage a sedentary lifestyle and disrupt natural sleep rhythms due to noise and shift changes. In fact, the best method we have for checking the whereabouts of patients in a psych ward, at night, is manually opening doors and waking them up. With requirements to log this information every fifteen or thirty minutes, studies have exposed this, "could be having the paradoxical effect of causing insomnia, worsening their mental health, as well as leading to incidents of aggression."

If the purpose of a building is to heal, as builders once believed, then it ought to support features that increase a patient's odds of returning to society: adequate sleep, regular exercise, eating well, believing in faith (e.g. future hope), a sense of connection and being in community.

These are the top priorities all designs need.

Safety & Tech

During free time my roommate and I would play cards. We would gossip about the other patients and nurses and tell stories. One day we noticed a man who walked our hallway frequently, that was not unusual, there were a lot of 'pacers' as we called them. One day the man stopped and peered into our room. We said hi, and he continued. My roommate got up and closed the door, for privacy I thought. She then told me a story. Her roommate before me was a young girl. This girl awoke in the middle of the night to this man standing over her bed with his pants down. She did not scream. The man left. Later the next day she found semen on her sheets and told the nurses.

Sleeping quarters should be separated by gender. To sleep well, one needs to feel safe. I never felt safe after knowing what happened to that young girl.

Common security measures today are cameras and locked doors. In designing for the future, there should be smoother integrations. Tracking monitors, whether embedded in a wearable device or other means, could enable such protection and agency. Patients wear bracelets with barcodes for pill disbursement. Why not add a location tracker and technology that registers biometric readings? Wearable devices could be used to monitor key health indicators, to better inform patients of their own health and habits. Incorporating data as part of a patient's education, truly making it personal, should also be an automatic part of care today. Why are the bodies of patients not better analyzed upon intake? Body composition, range of motion testing, along with nutritional profiling should become a standard.

Different kinds of patients should be afforded different levels of security. As a result, designing different access points to various (outdoor) opportunities should be standard. Confining all types of patients is efficient but not beneficial, because not all illnesses are the same. For patients with mania, it is necessary. For depressed individuals, confinement may be the worst thing. Let the anorexics hike. Give anxious patients endless bike rides. Keep the psychotics confined but let them breath fresh air. Modern tech can handle access routes and perimeter-setting.

Outside of biometric tracking, technology is underutilized in psychology. Neuroimaging is expensive. Artificial intelligence could automate administrative tasks, like documentation and paperwork, but future use of any robots is not well suited to the complexity of patient needs. In Japan, mood lighting is harnessed as a safety measure, with blue lights installed at certain unpopulated areas of train station platforms, as a form of suicide prevention. They are so successful that the UK is installing similar lighting. Japan's stations also hack riders' auditory senses in an effort to decrease stress. Music called hassha tunes are played during departures, cueing riders to impending closure. The effort to avert anxiety began decades ago after a train company hired composer Hiroaki Ide to create melodies. There is so much potential in applying technology, and music, in a care setting.

Exercise

There needs to be a gym. A yoga studio, dance floor, indoor and outdoor weights, bikes, a track field, basketball courts, even a pool. Though pools are expensive, the immersion of a body in water would do magical things—insurance and risk mitigation be damned! The mere act of jumping into a pool itself, or entering the steps, is therapy. When you enter water, you are transitioning from one element to another. It is uncomfortable. Once immersed, you may shiver, or jump up and down, trying to acclimate. Mentally, every time you enter a pool, you challenge yourself. That willpower is a worthy tool for patients to practice.

Doctors regularly prescribe exercise along with a sleep routine and hearty nutrition. John Ratey, an MD and clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, writes extensively on the topic in his book, Spark. Regular exercise, "can raise the baseline levels of dopamine and norepinephrine by spurring the growth of new receptors in certain brain areas." It does this by increasing blood flow, with each heartbeat, blood recycles waste and delivers oxygen and nutrients. Fresh blood is important for the brain, it delivers proteins, which drive the brain. During exercise muscles secrete essential molecules which improve cognitive processing (IGF-1: an insulin-like growth factor, VEGF: a vascular endothelial growth factor and ANP among others). Beyond cellular motives, exercise provides a release for the brain—distraction. In anxiety, exercise allows a person to focus on something besides fear. Ratey summarizes the benefits: a reduction of muscle tension, building of brain resources (GABA & BDNF: important for cementing alternative memories), rerouting of brain circuitry (via activation of sympathetic nervous system) which improves resilience and offers a sense of freedom that comes from movement. Movement is incredible, natural medicine.

But exercise is difficult for able-bodied people. For patients taking medication or already depressed, exercise is extra hard. The most attainable form is walking, which Hippocrates said is man's best medicine. Most psychiatric medications slow metabolism, make patients feel sedated, and increase weight gain. To successfully incorporate exercise as a habitual pattern, it needs to be easy, even fun. Imagine group workouts that vary in type, ranging from posture to stretching to yoga and cycling. Group walks and bike rides. Feeling the wind like in childhood, that nostalgic floating excitement with pedaling, and creating motion. Prisons have professionally led yoga programs. Why do psychiatric wards have none?

Spirituality

There needs to be a chapel. It can easily be non-denominational; we have excellent models like Mark Rothko's in Houston. Modernity needs to borrow from past psychiatric designs and make a space for faith. Studies claim that it fosters, "self-confidence, self-control, strength and hope…to correlate with increased self-efficacy." Hospitals have chapels. Even some jails have space that is set apart for prayer and religious purposes. Psych wards have largely been left out, though there are "chaplaincy programs" that incorporate faith into the healing journey, there are not many.

A physical place like a chapel would serve to inspire hope. All religions have their separate teachings and models. But a belief in something greater than the self offers perspective and a shift in mindset. Viktor Frankl talks about the self-sustaining qualities of hope in his book Man's Search for Meaning. He describes how looking to the future is sometimes the only thing that helps someone survive a dark time. Faith gives a framework to suffering.

Without requiring participation, or forcing an agenda, having a spiritual component to healing is possible to incorporate. The mind, body, will and soul are interwoven parts of a person. Thomas Aquinos said, "the soul is not contained by the body; rather it does contain the body." If the will represents the ability to choose, then the mind represents thoughts and feelings, our habitual patterns, and the body represents the ability to act. The word soul in Hebrew is "nephesh," and it means what we are. In Greek soul is psyche. It integrates the will, mind and body, and when these things are not aligned, we can feel it, life becomes exhausting. In psychology, this is called disassociation. Carl Jung famously believed the loss of religion was a factor in mental illness. He wrote: "Freud has unfortunately overlooked the fact that man has never yet been able single-handed to hold his own against the powers of the darkness—that is, of the unconscious. Man has always stood in need of the spiritual help which each individual's own religion held out to him…Man is never helped in suffering by what he thinks for himself, but only by revelations of a wisdom greater than his own."

Though DBT (Dialectical Behavior Therapy) and CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) teach concepts of emotional regulation through brain chemistry and signaling, the limbic system, self-acceptance and other logic—neither dip directly into spirituality. Transforming emotions and thoughts (e.g. neuroplasticity) would be greatly supported by offering an approach to living that was holistic. Religion, at minimum, gives us guidance on how to downplay self-worship and emphasizes service to community.

Animals

The Quakers promoted interactions with animals as part of healing and they ought to be used today. The science behind companionship animals is well known, they alleviate pain, reduce stress and anxiety, and can lower blood pressure and encourage social interaction. Certified dogs, cats, rabbits, horses and more—all wander the halls of hospitals already. Imagine a horse stable, dog run, or a hen house in close proximity to provide care to patients, as well as the routine of taking care of them (e.g. cleaning stalls, feeding, exercising, etc.). Animals drive neuroplasticity because they require new habits to be formed by their caretakers. They activate hormone and neurotransmitters like oxytocin ("the bonding hormone"), endorphins ("reduce pain and stress"), serotonin, dopamine and prolactin ("help regulate mood"). The amygdala is also activated during interactions, which regulates emotions and emotional learning. Animals provide a clear sense of purpose. If dog therapy is proven to improve mental health for inmates in prison, why hasn't anyone brought more than a support dog to visit a mental facility?

Visitors

Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler became famous for convincing his friends to drop the term dementia praecox and take up schizophrenia. He was also well known for socializing with his patients, hiking with them, arranging theatre productions and their financial planning. He understood recovery is rooted in connection with others.

Healthcare facilities ought to include space for visitors to stay as well, an adjacent hotel-like structure. Typical visits with family and friends are limited to once a day and usually restricted to under an hour. Especially if the care setting is located a distance away, making visitation plans easier would benefit all. People are greatly impacted when a loved one becomes ill. Support for them is often needed too. Together, opportunities like group therapy, hikes and other soulful activities can create many positive health benefits, and model best recovery habits for everyone.

We are not wired to live alone. Rates of recovery rise significantly with social support, especially from family members. American anthropologist Edward T. Hall once wrote, "'distance' connotes degrees of accessibility and also of concern. Human beings are interested in other people and in objects of importance to their livelihood. They want to know whether the significant others are far or near with respect to themselves and to each other." There is untapped comfort and medicine in being around those who know and support you in recovery.

Freedom in Confinement

America is in a tricky spot. The Los Angeles County jail is the largest mental health institution in the country. We have reverted back to rounding up the mentally ill and throwing them in prison. Though statistics say that those with a mental illness are not more likely to commit a crime, with substance abuse, conditions like schizophrenia do raise that likelihood.

We need the government to fix the problem it created. The solution is not one thing, it will continue to be many. When institutions grew so large, they became unsustainable, and we deinstitutionalized. Why didn't we keep both models—dedicated psychiatric hospitals and community care centers? We must maintain efforts at the community level, but we need to address the gapping chasm that is need of more space to serve inpatient care. At this time in history, that can only be solved by building more facilities.

Building is as expensive as it has ever been. It requires a lot of money. But the government is good at giving out a lot of money. In 2024, the state of California alone approved a $6.4 billion bond, with $4.4 billion dedicated to building behavioral health infrastructure including inpatient psychiatric facilities. The Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BHCIP) provides grants for constructing, acquiring or rehabilitating facilities that offer behavioral health services. Distributions vary from a few million to hundreds of millions, adding a few beds to hundreds of beds per project.

Adding thousands of new beds in California is great. But recall, historically, we have a deficit of roughly 465,000 beds excluding additional ones based on current population needs. Patients often rotate in and out of facilities, and if novel and personalized care can do anything to improve that, we could potentially decrease the need for future bed use.

Earlier this year debates roared when the government proposed the sale of millions of acres of land near parks, to private buyers. What if the government held onto ownership of the land, and allowed for a certain kind of development? If we have any chance of scaling construction for new facilities, we could allow development in these areas. We could create pre-approved architectural plans for various facility designs. We could incentivize builders with low interest loans and little to no rent bumps on ground leases, with hundred-year long terms. We could allow for private companies to cover the capital and risk of building. There could be contingencies baked into the recovery of their investment which ensure operating standards are met in the long-term. Mass timber is a competent product that honors natural landscaping and can compete head-to-head with any mid-rise concrete and steel structure, which is why lobbyists are fighting its regulation. Last year the government spent nearly $2 trillion on healthcare, the biggest budget item, in a balance sheet that is spiraling out of control. If there is ever a time to try something new—it's now.

Perhaps the government can kill zero birds with one stone, adding revenue with land development while scaling a new, improved model of inpatient mental healthcare.

We know a care setting needs walls. Though they should be built in the best way possible. Minds do not heal from medication alone, they need the body to move, to shift outside the self, and reconnect with others and Nature. Within a backdrop of that, freedom in confinement is possible.